Justice and Beauty. A Last, Full Measure

She was sharp. She was tough. She was deeply kind.She was resplendent in red.She was a loud, happy harmony of Italian-American toughness, soft skin and sweetness, belly laugher and beautiful, dark eyes. She was flirty. She was flinty. She was piercingly honest.She was uncompromising when it came to the truth. She understood what we generally call evil, but far more than that, she understood that we don't yet know exactly what evil is. With that blessed and rare knowledge, she knew we had to step lightly.But still, she knew, we had to step forward.Teresa Scalzo was the most accomplished and respected legal expert when it came to the prosecution of sexual violence in the U.S. She changed everything; the expertise she developed as a sex crimes prosecutor in her corner of northeastern Pennsylvania became first a national challenge and then a national standard. She came of age in a time when- understandably- some leaders of the anti-sexual violence movement were turning away from prosecution as an answer to sexual violence.Their objections to what we do were valid, of course. America, as I say increasingly in lectures, and as Teresa knew before me, doesn't have a criminal justice system. It has a criminal adjudication system. Justice is an ideal, a state of blessed balance in human interaction, a satisfying sense of rightness embedded somehow in our common ancestry. It's funny, actually; for all of the education and drilling we lawyers put ourselves through, what we end up striving for our entire professional lives is something toddlers grasp as they would a toy key ring. And yet this deeply human, deeply shared sense of simple rightness is also as elusive as a rainbow.The elusiveness of justice is no more pronounced then where crimes of sexual violence are concerned. The subject itself- sex- is hopelessly tangled in thousands of years of mystery and shame, pleasure and violence, life and death. There has never been a phenomenon so central to human existence and yet so shrouded, so guarded, so punished. The punishers have been- cross culturally- mostly men. For millennia they've been simultaneously intoxicated by and terrified of the power of women. It's been less even about sex than about the female embodiment of it, the women who bled but did not die, who brought forth life from swollen bellies and then fed it from their breasts, these goddesses who could erase the mind of a conqueror with a smile, or a frown. These creatures, the thinking has gone, must be controlled. Demonized. Marginalized. Our desire for them, the thinking has gone, must be projected. Sanitized. Excused.Teresa understood these dynamics. The ancient ones. The current ones. The fact that they're all really the same. What she fought for most ardently, though, was the redemption of the only system we have- in the most advanced society in the world- to deal with sexual violence. Teresa fought for the relevance of prosecution to the fight against rape. She did this not because she thought the system was perfect or ever could be; rather, she fought for it because she knew it was all we have. The law, at bottom, is our only living embodiment of the public will. For rape victims, the civilized response is about the system we have: The police, the advocates, the nurses, the prosecutors. Teresa looked at this system, and she knew she could make it better.She was right.Our system is far better now then when Teresa Scalzo started to make it better. It has a long way to go, but every step it takes moving forward, it takes with her legacy as its power.I was in awe of this woman, this goddess, this marvelous mixture of seriousness and red wine hangovers, of wisdom and joy, of scholarship and instinct, of hope and frustration. She taught me everything. She vouched for me as a man in a woman's world, which was so ironic because we both initially inhabited a man's world- prosecution- that Teresa nevertheless took over where sexual assault was concerned through will, sincerity and raw skill.I strove every day to keep in step with her, always behind but always inspired.And then she died. But not before giving the last, full measure of everything she was- and dear God that was so much- to what we do in the service of the women and men whose lives are torn apart by sexual violence. What we do now, we do largely in her honor, and through her legacy.I know now in middle age what an elusive ideal justice is, and I am sadder for it. But I also know what beauty is. I know how the shadows of existence are shot through with it, and how it expresses itself to us, as I believe God does.T, you were beautiful. Thank you.

She was sharp. She was tough. She was deeply kind.She was resplendent in red.She was a loud, happy harmony of Italian-American toughness, soft skin and sweetness, belly laugher and beautiful, dark eyes. She was flirty. She was flinty. She was piercingly honest.She was uncompromising when it came to the truth. She understood what we generally call evil, but far more than that, she understood that we don't yet know exactly what evil is. With that blessed and rare knowledge, she knew we had to step lightly.But still, she knew, we had to step forward.Teresa Scalzo was the most accomplished and respected legal expert when it came to the prosecution of sexual violence in the U.S. She changed everything; the expertise she developed as a sex crimes prosecutor in her corner of northeastern Pennsylvania became first a national challenge and then a national standard. She came of age in a time when- understandably- some leaders of the anti-sexual violence movement were turning away from prosecution as an answer to sexual violence.Their objections to what we do were valid, of course. America, as I say increasingly in lectures, and as Teresa knew before me, doesn't have a criminal justice system. It has a criminal adjudication system. Justice is an ideal, a state of blessed balance in human interaction, a satisfying sense of rightness embedded somehow in our common ancestry. It's funny, actually; for all of the education and drilling we lawyers put ourselves through, what we end up striving for our entire professional lives is something toddlers grasp as they would a toy key ring. And yet this deeply human, deeply shared sense of simple rightness is also as elusive as a rainbow.The elusiveness of justice is no more pronounced then where crimes of sexual violence are concerned. The subject itself- sex- is hopelessly tangled in thousands of years of mystery and shame, pleasure and violence, life and death. There has never been a phenomenon so central to human existence and yet so shrouded, so guarded, so punished. The punishers have been- cross culturally- mostly men. For millennia they've been simultaneously intoxicated by and terrified of the power of women. It's been less even about sex than about the female embodiment of it, the women who bled but did not die, who brought forth life from swollen bellies and then fed it from their breasts, these goddesses who could erase the mind of a conqueror with a smile, or a frown. These creatures, the thinking has gone, must be controlled. Demonized. Marginalized. Our desire for them, the thinking has gone, must be projected. Sanitized. Excused.Teresa understood these dynamics. The ancient ones. The current ones. The fact that they're all really the same. What she fought for most ardently, though, was the redemption of the only system we have- in the most advanced society in the world- to deal with sexual violence. Teresa fought for the relevance of prosecution to the fight against rape. She did this not because she thought the system was perfect or ever could be; rather, she fought for it because she knew it was all we have. The law, at bottom, is our only living embodiment of the public will. For rape victims, the civilized response is about the system we have: The police, the advocates, the nurses, the prosecutors. Teresa looked at this system, and she knew she could make it better.She was right.Our system is far better now then when Teresa Scalzo started to make it better. It has a long way to go, but every step it takes moving forward, it takes with her legacy as its power.I was in awe of this woman, this goddess, this marvelous mixture of seriousness and red wine hangovers, of wisdom and joy, of scholarship and instinct, of hope and frustration. She taught me everything. She vouched for me as a man in a woman's world, which was so ironic because we both initially inhabited a man's world- prosecution- that Teresa nevertheless took over where sexual assault was concerned through will, sincerity and raw skill.I strove every day to keep in step with her, always behind but always inspired.And then she died. But not before giving the last, full measure of everything she was- and dear God that was so much- to what we do in the service of the women and men whose lives are torn apart by sexual violence. What we do now, we do largely in her honor, and through her legacy.I know now in middle age what an elusive ideal justice is, and I am sadder for it. But I also know what beauty is. I know how the shadows of existence are shot through with it, and how it expresses itself to us, as I believe God does.T, you were beautiful. Thank you.

Honored Beyond Words: Being a Part of "Lived Through This"

It has to have been 8 years or more since I first heard of the Voices and Faces Project, although it seems like much longer. Its mission is so beautifully simple that it tends to transcend its also beautifully simple name: Voices and Faces.But that’s the point.The best prosecutors, investigators and advocates I ever worked with in this business knew that the word “case,” and the dozens of other words we use to categorize, triage, sanitize and process human misery as a result of crime, was a reprehensible substitute for the person we came to know at the center of it.Yes, it was a case, and it had to be dealt with as such. But the thing that haunted us wasn’t the case. It was the she or he, the unique, mysterious, and sometimes broken, sometimes remarkably unbowed, person before us. To the extent we were responsible to her or him- at least for what we could control in the almost comically blunt and fractured, imperfect system we worked in- we struggled to keep that person’s face foremost in our minds. We struggled to hear her or his voice as we strategized, made decisions, and dealt out “justice” as we’d been conditioned to accept and define it.But even that voice- the one we heard- was truncated. I was good at what I did, and I listened well. But what I needed to hear professionally, and what I could spare the time and emotional energy for, was always far less than what could have been fully related to me. When I parted ways with a survivor, whether she was 5 or 75, I often wondered what I’d missed, and was missing then and forever. But it wasn't something I could dwell on. There were more "cases" coming in. Pretty much every day.The pinnacle of what I did wasn’t winning those cases (and yes, I accept how self-serving that sounds, having lost my share). Regardless, the pinnacle was responding to the voices and acknowledging the faces in a way that gave them- and not us- the measure of dignity and recognition they deserved.That is the day to day challenge that simply must be met in the Anglo-American criminal justice response to sexual violence, or all else is lost, and our critics are right to say we serve no one but ourselves.But even at our best, we could only see so much, and absorb so much. There was- and always will be- an ocean of human experience going woefully unnoticed by those of us tasked with responding professionally to the harm done. We’re simply not equipped to know it all, whether because it’s not legally relevant, not immediately discernible, or not emotionally digestible given the spectrum we work on.And the saddest fact, of course, is that the incalculable amount of suffering, resilience, inspiration and courage that results from sexual violence in our world could be at any time multiplied exponentially from what I missed, and that all of us in the entire system miss. This is because we only see what enters the system we created in the first place. The vast, vast majority of sexual violence that occurs the world over, day in and day out, is never revealed to any sort of system of authority or adjudication. It simply goes unmet, unaided, unanswered. Unheard.Voices and Faces changes that, and with no more than the courage of the survivors and the ability to memorialize their accounts. Of course, the project stands apart from the criminal justice response and well it should. I simply came across it as a practitioner with no other perspective.Except for one. I am a victim, myself of child sexual abuse, a fact known now to most who know me in any capacity, but unknown to most during my tenure as a special victims prosecutor. A few years ago, the author of “Lived Through This,” herself a survivor of a brutal home invasion rape and a dear friend, approached me about being a part of the compilation she envisioned. She knew my story. She wanted to tell it for me. The proudest thing I’ve ever done is to allow her to do so.Thank you, Anne, for doing it so very beautifully.

It has to have been 8 years or more since I first heard of the Voices and Faces Project, although it seems like much longer. Its mission is so beautifully simple that it tends to transcend its also beautifully simple name: Voices and Faces.But that’s the point.The best prosecutors, investigators and advocates I ever worked with in this business knew that the word “case,” and the dozens of other words we use to categorize, triage, sanitize and process human misery as a result of crime, was a reprehensible substitute for the person we came to know at the center of it.Yes, it was a case, and it had to be dealt with as such. But the thing that haunted us wasn’t the case. It was the she or he, the unique, mysterious, and sometimes broken, sometimes remarkably unbowed, person before us. To the extent we were responsible to her or him- at least for what we could control in the almost comically blunt and fractured, imperfect system we worked in- we struggled to keep that person’s face foremost in our minds. We struggled to hear her or his voice as we strategized, made decisions, and dealt out “justice” as we’d been conditioned to accept and define it.But even that voice- the one we heard- was truncated. I was good at what I did, and I listened well. But what I needed to hear professionally, and what I could spare the time and emotional energy for, was always far less than what could have been fully related to me. When I parted ways with a survivor, whether she was 5 or 75, I often wondered what I’d missed, and was missing then and forever. But it wasn't something I could dwell on. There were more "cases" coming in. Pretty much every day.The pinnacle of what I did wasn’t winning those cases (and yes, I accept how self-serving that sounds, having lost my share). Regardless, the pinnacle was responding to the voices and acknowledging the faces in a way that gave them- and not us- the measure of dignity and recognition they deserved.That is the day to day challenge that simply must be met in the Anglo-American criminal justice response to sexual violence, or all else is lost, and our critics are right to say we serve no one but ourselves.But even at our best, we could only see so much, and absorb so much. There was- and always will be- an ocean of human experience going woefully unnoticed by those of us tasked with responding professionally to the harm done. We’re simply not equipped to know it all, whether because it’s not legally relevant, not immediately discernible, or not emotionally digestible given the spectrum we work on.And the saddest fact, of course, is that the incalculable amount of suffering, resilience, inspiration and courage that results from sexual violence in our world could be at any time multiplied exponentially from what I missed, and that all of us in the entire system miss. This is because we only see what enters the system we created in the first place. The vast, vast majority of sexual violence that occurs the world over, day in and day out, is never revealed to any sort of system of authority or adjudication. It simply goes unmet, unaided, unanswered. Unheard.Voices and Faces changes that, and with no more than the courage of the survivors and the ability to memorialize their accounts. Of course, the project stands apart from the criminal justice response and well it should. I simply came across it as a practitioner with no other perspective.Except for one. I am a victim, myself of child sexual abuse, a fact known now to most who know me in any capacity, but unknown to most during my tenure as a special victims prosecutor. A few years ago, the author of “Lived Through This,” herself a survivor of a brutal home invasion rape and a dear friend, approached me about being a part of the compilation she envisioned. She knew my story. She wanted to tell it for me. The proudest thing I’ve ever done is to allow her to do so.Thank you, Anne, for doing it so very beautifully.

Needed Wisdom on Rape from a Former Judge

"We were insulted by the word "date" rape. "Date" rape does not exist. It's a misnomer; It's like saying "car-jack." Car-jack is robbery. Rape is rape. That's it."-former judge Robert Holdman on his time as Chief Trial Counsel, Child Abuse and Sex Unit, Bronx District Attorneys Office, Bronx, New YorkA colleague and mentor, former New York State Supreme Court Justice Robert Holdman, was invited to participate in a Huffpost Live broadcast on the Steubenville rape case as the trial was being heard. He was joined by Alexander Abad Santos of the Atlantic Wire, and also Zerlina Maxwell and Jaclyn Friedman. Friedman and Maxwell in particular are well-known warriors in the fight against rape culture, and I've had the honor of working with and learning from Jaclyn personally. The broadcast is an excellent discussion of the Steubenville dynamics and the larger problem beyond it. It's still well worth watching even as the case fades slowly away from the news cycle.What made Holdman's comments so important is that they came from the perspective of a former trial judge. While most U.S. judges are honorable professionals worthy of the power of the robe, the judiciary is still a place where we don't see enough understanding of the dynamics and reality of sexual violence. This is particularly true with non-stranger sexual violence, the kind women and men experience far more than any other.Every criminal defendant deserves a full and robust defense, and also a judge who is sensitive to the circumstances of an individual facing the power of the government, regardless of the charges. Holdman would surely agree, and his comments rightfully included the responsibility of judges to be neutral and fair to defendants facing criminal prosecution. Being a good trial judge doesn't mean- from my perspective or any other- assuming guilt in any criminal case or anything close to it. But an ignorance of the reality of sexual violence, particularly between individuals who know each other, and an over-reliance on the myth and innuendo so pervasive in our culture regarding rape and sexual assault, lead far too many judges to render irrational and unjust decisions in these types of cases.Important professional opportunities have taken Holdman- for now- from his duties as a trial judge. Still, I hope the messages he has conveyed reach the men and women who make the crucial decisions that shape sexual violence cases nationwide and beyond. I also hope he finds his way back to the bench as his career progresses; his kind of clarity on this subject needs to be as common on the judicial bench as it needs to be everywhere else.

"We were insulted by the word "date" rape. "Date" rape does not exist. It's a misnomer; It's like saying "car-jack." Car-jack is robbery. Rape is rape. That's it."-former judge Robert Holdman on his time as Chief Trial Counsel, Child Abuse and Sex Unit, Bronx District Attorneys Office, Bronx, New YorkA colleague and mentor, former New York State Supreme Court Justice Robert Holdman, was invited to participate in a Huffpost Live broadcast on the Steubenville rape case as the trial was being heard. He was joined by Alexander Abad Santos of the Atlantic Wire, and also Zerlina Maxwell and Jaclyn Friedman. Friedman and Maxwell in particular are well-known warriors in the fight against rape culture, and I've had the honor of working with and learning from Jaclyn personally. The broadcast is an excellent discussion of the Steubenville dynamics and the larger problem beyond it. It's still well worth watching even as the case fades slowly away from the news cycle.What made Holdman's comments so important is that they came from the perspective of a former trial judge. While most U.S. judges are honorable professionals worthy of the power of the robe, the judiciary is still a place where we don't see enough understanding of the dynamics and reality of sexual violence. This is particularly true with non-stranger sexual violence, the kind women and men experience far more than any other.Every criminal defendant deserves a full and robust defense, and also a judge who is sensitive to the circumstances of an individual facing the power of the government, regardless of the charges. Holdman would surely agree, and his comments rightfully included the responsibility of judges to be neutral and fair to defendants facing criminal prosecution. Being a good trial judge doesn't mean- from my perspective or any other- assuming guilt in any criminal case or anything close to it. But an ignorance of the reality of sexual violence, particularly between individuals who know each other, and an over-reliance on the myth and innuendo so pervasive in our culture regarding rape and sexual assault, lead far too many judges to render irrational and unjust decisions in these types of cases.Important professional opportunities have taken Holdman- for now- from his duties as a trial judge. Still, I hope the messages he has conveyed reach the men and women who make the crucial decisions that shape sexual violence cases nationwide and beyond. I also hope he finds his way back to the bench as his career progresses; his kind of clarity on this subject needs to be as common on the judicial bench as it needs to be everywhere else.

10 Years in Iraq: The Fragrance of Flowers. The Horror of War. The Burden of Doing Justice in its Wake

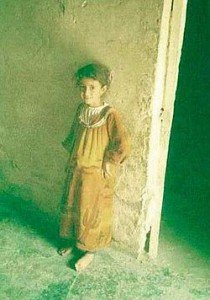

Note to readers: The post below was one I wrote not in anticipation of the 10th anniversary of the US invasion of Iraq, but an anniversary of the atrocities at Al-Mahmudiyah. I've since realized the post is more appropriate for publication at a significant anniversary of the invasion. The reason is simple: The atrocities at Mahmudiyah are as intrinsic and foreseeable an aspect of war as any that can be imagined. The designers of the war must never be allowed to escape that.“Abeer” translates in Arabic to “the fragrance of flowers” and was the name given to the 14 year-old girl ruthlessly raped and murdered, along with her parents and six year-old sister, on March 12, 2006, near the town of Al-Mahmudiyah, Iraq. The murderers were a group of American soldiers, stationed at a nearby checkpoint in an especially brutal time after the American invasion three years previous.Of the many honorable men and women I met serving as a civilian in the Army JAG Corps, the one I came to know the best was among the first and most involved prosecutors in the Al-Mahmudiyah massacre. It wasn’t enough that he endured a difficult and dangerous deployment as part of the 101st Airborne Division. He was also saddled with bringing, of all things, the weight of that crime home with him as he handled the case near Fort Campbell, Kentucky. He did this while readjusting to stateside and family life as a husband and father. He’ll acknowledge that burden if it’s pointed out. But he will never, ever complain about it. First, because by God’s grace, his own family is intact and healthy, and he was able to hold them when he returned. Second, because seeking justice for Abeer and her family was an honor he accepted with humility and a deep sense of duty that I found typical in the Army JAG Corps. He sought justice for his Army and his country. But I suspect most of all he sought justice for for Abeer, and the details he came to know of her life and the unspeakable circumstances of her death.The details are public, if you want them. I can tell you that nightmares are all you’re likely to get for mining them, and I say this as a trained absorber of such things.The Army JAG Corps ignored several things I encouraged them to address while I served as a consultant. In a time where soldier suicides are spiking in particular, perhaps the most puzzling to me was refusing (to my knowledge and based on their responses to me at the time) to even look into proactive assistance for JAG prosecutors and defenders who must absorb, if not horrors like Mahmudiyah on a daily basis, then things like increasingly detailed and technologically advanced videos of children used in pornography or worse.And then there is war, the ones we’ve been waging now on the backs of a volunteer military and its valiant but exhausted support bulwark for nearly 12 years. Among myriad other things, war requires the prosecution and defense of combatants accused of atrocities and horrors more regularly than many grasp.I blame Mahmudiyah solely on the men who conceived and carried it out. They represent nothing but themselves; not the US Army, not the stress of combat (which the vast majority of soldiers endure without resorting to murder and rape) and not even the war itself. Regardless, the men and women who must address legally what military conflict inevitably produces must be cared for during that process. Of its many poisons, war vomits things like Mahmudiyah regularly. It did so at Fort Pillow, Tennessee, at My Lai,Quan Ngai, in Kandahar, Afghanistan. It has done so in every war and under every flag unfurled since the beginning of combat.The architects of the 2003 Iraq War, just as the drum-beaters for Vietnam, may argue with scholarly confidence that they were right, or with grave regret that they were wrong. But none may claim a lack of foreseeability for one single thing that occurred or will occur as a result of their decisions. No act, no matter how shocking, how damning, how soul-crushing and freakishly inhuman, is unforeseeable the moment war is engaged.Similarly, the stress of sorting out, in courts of military justice, the details of anything war yields is also foreseeable and addressable. It’s not enough to own, no matter how deeply, what war really is. We must also support appropriately those who must seek justice in its wake.

Note to readers: The post below was one I wrote not in anticipation of the 10th anniversary of the US invasion of Iraq, but an anniversary of the atrocities at Al-Mahmudiyah. I've since realized the post is more appropriate for publication at a significant anniversary of the invasion. The reason is simple: The atrocities at Mahmudiyah are as intrinsic and foreseeable an aspect of war as any that can be imagined. The designers of the war must never be allowed to escape that.“Abeer” translates in Arabic to “the fragrance of flowers” and was the name given to the 14 year-old girl ruthlessly raped and murdered, along with her parents and six year-old sister, on March 12, 2006, near the town of Al-Mahmudiyah, Iraq. The murderers were a group of American soldiers, stationed at a nearby checkpoint in an especially brutal time after the American invasion three years previous.Of the many honorable men and women I met serving as a civilian in the Army JAG Corps, the one I came to know the best was among the first and most involved prosecutors in the Al-Mahmudiyah massacre. It wasn’t enough that he endured a difficult and dangerous deployment as part of the 101st Airborne Division. He was also saddled with bringing, of all things, the weight of that crime home with him as he handled the case near Fort Campbell, Kentucky. He did this while readjusting to stateside and family life as a husband and father. He’ll acknowledge that burden if it’s pointed out. But he will never, ever complain about it. First, because by God’s grace, his own family is intact and healthy, and he was able to hold them when he returned. Second, because seeking justice for Abeer and her family was an honor he accepted with humility and a deep sense of duty that I found typical in the Army JAG Corps. He sought justice for his Army and his country. But I suspect most of all he sought justice for for Abeer, and the details he came to know of her life and the unspeakable circumstances of her death.The details are public, if you want them. I can tell you that nightmares are all you’re likely to get for mining them, and I say this as a trained absorber of such things.The Army JAG Corps ignored several things I encouraged them to address while I served as a consultant. In a time where soldier suicides are spiking in particular, perhaps the most puzzling to me was refusing (to my knowledge and based on their responses to me at the time) to even look into proactive assistance for JAG prosecutors and defenders who must absorb, if not horrors like Mahmudiyah on a daily basis, then things like increasingly detailed and technologically advanced videos of children used in pornography or worse.And then there is war, the ones we’ve been waging now on the backs of a volunteer military and its valiant but exhausted support bulwark for nearly 12 years. Among myriad other things, war requires the prosecution and defense of combatants accused of atrocities and horrors more regularly than many grasp.I blame Mahmudiyah solely on the men who conceived and carried it out. They represent nothing but themselves; not the US Army, not the stress of combat (which the vast majority of soldiers endure without resorting to murder and rape) and not even the war itself. Regardless, the men and women who must address legally what military conflict inevitably produces must be cared for during that process. Of its many poisons, war vomits things like Mahmudiyah regularly. It did so at Fort Pillow, Tennessee, at My Lai,Quan Ngai, in Kandahar, Afghanistan. It has done so in every war and under every flag unfurled since the beginning of combat.The architects of the 2003 Iraq War, just as the drum-beaters for Vietnam, may argue with scholarly confidence that they were right, or with grave regret that they were wrong. But none may claim a lack of foreseeability for one single thing that occurred or will occur as a result of their decisions. No act, no matter how shocking, how damning, how soul-crushing and freakishly inhuman, is unforeseeable the moment war is engaged.Similarly, the stress of sorting out, in courts of military justice, the details of anything war yields is also foreseeable and addressable. It’s not enough to own, no matter how deeply, what war really is. We must also support appropriately those who must seek justice in its wake.

Virginia, Blood and Soil

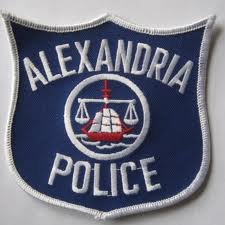

Through five European dominated centuries, Virginia soil has been stained red time and time again. The Civil War alone drew so much blood- along the turnpikes and rivers, in the killing fields and tree lines- it's a wonder it wasn't coughed up by the tired, stomped-on ground tasked with absorbing it.Within eight days of each other this month, the blood of two men, both police officers, again stained Virginia ground in two places quite familiar with its presence. One occurred in Alexandria, the contested and then occupied port city just south of Washington, and one in Dinwiddie County, southeast of Petersburg and cross-hatched within the brutal conquest of Richmond and then the Confederacy.One man lost his life at the scene. The other, thankfully, clings to life.I know Peter Laboy, the officer shot in Alexandria on a traffic stop who, as of this writing, thankfully survives and improves. We were rookies at exactly the same time in early 1997, him of the Alexandria Police Department and me as an Assistant Commonwealth's Attorney. As I learned to prosecute Driving While Intoxicated cases, Peter was learning to write them up; I would spend time with him on nights I was riding along with the evening and midnight divisions in search of drunk drivers. He was kind, boyish and soft-spoken in those days, not yet possessed of the confidence I imagine he has now as a veteran of the city's elite motor unit.I did not know Junius Walker, the Master Trooper and 35 year-veteran of the Virginia State Police who was shot and killed when he stopped to assist a motorist along I-85. He seems like a fine man and exactly the kind of cop who made me truly enjoy the interaction I had with police officers and state troopers over the years. I do know well the desolate, wooded stretch of road he was killed along, and I doubt I will travel it again without thinking of him. By God's design we all return to the earth, bones and flesh to dust again. But a somber salute should be offered to these two men who most recently gave early to the earth precious blood in service to their Commonwealth. May that already hallowed ground not be burdened again with the red stain of violence for a long, long time.

Through five European dominated centuries, Virginia soil has been stained red time and time again. The Civil War alone drew so much blood- along the turnpikes and rivers, in the killing fields and tree lines- it's a wonder it wasn't coughed up by the tired, stomped-on ground tasked with absorbing it.Within eight days of each other this month, the blood of two men, both police officers, again stained Virginia ground in two places quite familiar with its presence. One occurred in Alexandria, the contested and then occupied port city just south of Washington, and one in Dinwiddie County, southeast of Petersburg and cross-hatched within the brutal conquest of Richmond and then the Confederacy.One man lost his life at the scene. The other, thankfully, clings to life.I know Peter Laboy, the officer shot in Alexandria on a traffic stop who, as of this writing, thankfully survives and improves. We were rookies at exactly the same time in early 1997, him of the Alexandria Police Department and me as an Assistant Commonwealth's Attorney. As I learned to prosecute Driving While Intoxicated cases, Peter was learning to write them up; I would spend time with him on nights I was riding along with the evening and midnight divisions in search of drunk drivers. He was kind, boyish and soft-spoken in those days, not yet possessed of the confidence I imagine he has now as a veteran of the city's elite motor unit.I did not know Junius Walker, the Master Trooper and 35 year-veteran of the Virginia State Police who was shot and killed when he stopped to assist a motorist along I-85. He seems like a fine man and exactly the kind of cop who made me truly enjoy the interaction I had with police officers and state troopers over the years. I do know well the desolate, wooded stretch of road he was killed along, and I doubt I will travel it again without thinking of him. By God's design we all return to the earth, bones and flesh to dust again. But a somber salute should be offered to these two men who most recently gave early to the earth precious blood in service to their Commonwealth. May that already hallowed ground not be burdened again with the red stain of violence for a long, long time.

Courage: An Army Rape Survivor Speaks Out

An important blog called My Duty to Speak exists to give military sexual violence survivors a forum to share their experiences. The one shared most recently is particularly haunting. An unrelated hazing incident after the attack added further trauma. But nothing equals the apparent confession the attacker made during an "amnesty day" in front of drill sergeants who took no action. Incidents like this underpin, among other things, an alarming suicide rate. Good on this person for possessing the courage to come forward and speak up.

Mark Hasse, Lay At Rest, And With Honor

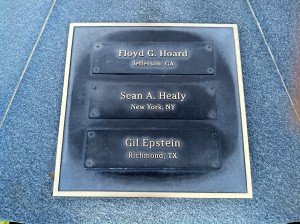

In the courtyard of the National Advocacy Center, the premier US training facility for prosecutors in Columbia, South Carolina, there is a monument to prosecuting attorneys who have been killed in relation to their official duties. A section of it is shown above, including the name of Sean Healy, a bright, rookie ADA in the Bronx, New York who was gunned down senselessly in August of 1990 near the same office I worked in on E. 161st Street.Fallen prosecutors constitue an honored and thankfully small group. Like judges, they aren't frequently targeted by the defendants they interact with in court. Most criminals consider the justice process a cost of doing business. Over the years I encountered men I prosecuted, whether successfully or not, in the communities where I lived and worked, sometimes months or years after the fact. The vast majority were polite and cordial, some actually friendly. Where they were concerned, it wasn't personal. And they were right; even in my work where facts can be horrific and emotions run high, it wasn't.I got one death threat in over ten years as a trial attorney that I thought was credible. It arose out of a misdemeanor domestic violence case I tried that was from my perspective unremarkable. I'm sure it had little to do with me as the prosecutor and more to do with the wandering focus of the defendant who threatened a few times to kill me, once on a DC street where I somehow crossed his path on the way to a hockey game with a friend. For a while I ignored it, until one day at a post-trial hearing where he stared at me until he caught my eye, then drew his index finger over his throat and pointed at me. At that point I told Randy Sengel, the Commonwealth's Attorney for the City of Alexandria, Virginia where I was then a junior ACA. Randy is a deeply respected, honorable public servant and brilliant man, but perhaps known most for his sphinx-like reticence and un-rattled, deadpan approach to just about everything. When I gave him the details, he told me it was rare but that it happened, and that I should call a detective nicknamed Scotty and make a report.But Scotty was a homicide detective, I pointed out."Yeah," Randy said with a shrug. "If someone threatens your life, that's what you do."I made the report, Detective Scott did his job, the guy eventually turned his focus elsewhere, and I'm still here. Mark Hasse, a veteran and apparently well-respected assistant district attorney from near Dallas, Texas, is not. Hasse was gunned down, execution style, outside of his office last week, very possibly in relation to his duties as a felony ADA. Investigators are searching desperately for answers, but eight days later they appear to remain elusive. He will be laid to rest tomorrow. Hasse appears to have been a valued prosecutor and a well-liked figure in both the courtroom and the community. If his service was cut short by murderers out to silence him and and thwart the process he sought to uphold, that act is indeed "an attack on our criminal justice system" as a Texas judge referred to it. Targeting those in the system, whether police, prosecutors, judges, defense attorneys or jurors, is the final assault on the rule of law.Of course, front line responders like police officers remain in far more danger. I drove extensively through Southern California this past week and was sobered to see how many highways are dedicated to members of the California Highway Patrol who died in the line. For now, at least, most of us in the system who practice law are far safer in our duties. Still, if Hasse was killed in the name of blurring the line between civil society and what lies beneath, then everyone- within Kaufman, Texas and far beyond- should be gravely concerned.

In the courtyard of the National Advocacy Center, the premier US training facility for prosecutors in Columbia, South Carolina, there is a monument to prosecuting attorneys who have been killed in relation to their official duties. A section of it is shown above, including the name of Sean Healy, a bright, rookie ADA in the Bronx, New York who was gunned down senselessly in August of 1990 near the same office I worked in on E. 161st Street.Fallen prosecutors constitue an honored and thankfully small group. Like judges, they aren't frequently targeted by the defendants they interact with in court. Most criminals consider the justice process a cost of doing business. Over the years I encountered men I prosecuted, whether successfully or not, in the communities where I lived and worked, sometimes months or years after the fact. The vast majority were polite and cordial, some actually friendly. Where they were concerned, it wasn't personal. And they were right; even in my work where facts can be horrific and emotions run high, it wasn't.I got one death threat in over ten years as a trial attorney that I thought was credible. It arose out of a misdemeanor domestic violence case I tried that was from my perspective unremarkable. I'm sure it had little to do with me as the prosecutor and more to do with the wandering focus of the defendant who threatened a few times to kill me, once on a DC street where I somehow crossed his path on the way to a hockey game with a friend. For a while I ignored it, until one day at a post-trial hearing where he stared at me until he caught my eye, then drew his index finger over his throat and pointed at me. At that point I told Randy Sengel, the Commonwealth's Attorney for the City of Alexandria, Virginia where I was then a junior ACA. Randy is a deeply respected, honorable public servant and brilliant man, but perhaps known most for his sphinx-like reticence and un-rattled, deadpan approach to just about everything. When I gave him the details, he told me it was rare but that it happened, and that I should call a detective nicknamed Scotty and make a report.But Scotty was a homicide detective, I pointed out."Yeah," Randy said with a shrug. "If someone threatens your life, that's what you do."I made the report, Detective Scott did his job, the guy eventually turned his focus elsewhere, and I'm still here. Mark Hasse, a veteran and apparently well-respected assistant district attorney from near Dallas, Texas, is not. Hasse was gunned down, execution style, outside of his office last week, very possibly in relation to his duties as a felony ADA. Investigators are searching desperately for answers, but eight days later they appear to remain elusive. He will be laid to rest tomorrow. Hasse appears to have been a valued prosecutor and a well-liked figure in both the courtroom and the community. If his service was cut short by murderers out to silence him and and thwart the process he sought to uphold, that act is indeed "an attack on our criminal justice system" as a Texas judge referred to it. Targeting those in the system, whether police, prosecutors, judges, defense attorneys or jurors, is the final assault on the rule of law.Of course, front line responders like police officers remain in far more danger. I drove extensively through Southern California this past week and was sobered to see how many highways are dedicated to members of the California Highway Patrol who died in the line. For now, at least, most of us in the system who practice law are far safer in our duties. Still, if Hasse was killed in the name of blurring the line between civil society and what lies beneath, then everyone- within Kaufman, Texas and far beyond- should be gravely concerned.

Thank You, Dan McCarthy

“The qualities of a good prosecutor are as elusive and as impossible to define as those which make a gentleman. And those who need to be told would not understand it anyway. A sensitiveness to fair play and sportsmanship is perhaps the best protection against the abuse of power, and the citizens safety lies in the prosecutor who tempers zeal with human kindness, who seeks truth and not victims, who serves the law and not factional purposes, and who approaches his task with humility.”Robert H. Jackson, United States Supreme Court Justice, 1940This quote adorns the plaque with my badge affixed to it, given to me by Randy Sengel, Commonweatlth's Attorney for the City of Alexandria, Virginia when I left the office in 2003. It is a sentiment I've seen embodied in a happily large number of men and women over the course of my career, but perhaps never so profoundly as in a friend who passed away unexpectedly this week, Dan McCarthy.It's been observed in the legal community that, oftentimes, there's an inverse relationship between the skill and success of a trial attorney, and his or her skill and success as a human being. Simply put, some of the most effective and remarkably talented trial attorneys out there are walking disasters in their personal lives.Daniel McCarthy, Chief Trial Counsel and Director of Trial Training at the Bronx District Attorneys Office, was the very best trial lawyer I ever knew personally, and recognized as one of the best in the country. He was also a remarkable success as a human being. Dan could do both, and with what looked like effortless aplomb.I worked in the Bronx, where Dan was an ADA for 18 years, for a little less than two. When I contemplate my service there I sometimes feel the guilt of soldiers who, for whatever reason, spent very little time in a combat zone. I am grateful for the experience, but I hold my service cheap compared to friends, colleagues and giants like Dan who spent much of their careers in service in this good and fascinating, but often brutal and challenging community. Dan had every opportunity to leave prosecution almost 20 years ago and make a remarkably good living as a litigator in the private sector. But instead he went from one tough environment (Queens) to an arguably even tougher environment (the Bronx) in order to continue to seek justice and serve victims.Thankfully I knew Dan before and after BXDA, but during my time there he taught me things I still hold dear. My favorite example might be this one: ADA's, when they appear in court, usually announce their appearance for the "District Attorney." It was Dan who taught me to personalize my appearance to the good man who hired me. "He represents this community and he deserves your loyalty and respect," he said. "When you appear in court, say you're there on behalf of the office of Robert T. Johnson." It was a gesture I maintained when I appeared on behalf of then Attorney General Andrew M. Cuomo two years later.It was Dan- more than anyone else in my career, and I have had great mentors- who emphasized in deeply compassionate terms the reality that lingered behind the case folders. Lives are broken by crime and they are not put back together by criminal litigation. The dead are silenced and their potential truncated, leaving behind grieving loved ones who never fully recover. The wounded and paralyzed- mentally or physically- are at times left to navigate lives that can draw out like a blade in numbing, endless days of struggle. Victims fight nightmares, despair, hopelessness and rage, all long after the publicity is over, the juries are dismissed and the accolades are shared. Dan never let us forget this.The Bronx, at once magnificent and godforsaken, lush with green space and choked with urban density, home to centuries of history and yesterday's arrivals from every point on the globe, possessed of both world-class schools and grinding poverty, is itself a study in contradictions.When I think about it, I suppose Dan was also. He was a nationally known attorney with sobering responsibilities who was always ready to poke fun at himself and never too busy to brainstorm with a young ADA facing a first larceny trial. He was endlessly creative, pincer-like and pulverizing when proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, but hyper-ethical and deeply compassionate to everyone on both sides of the tragic cases he handled. He was erudite and analytical but fun-loving and folksy. The man could, very simply, do it all. His loss leaves an empty space in the American prosecution community and the lives of his friends and family that won't be filled. But he also leaves a legacy of decency, compassion and justice that will, in the spirit of true success, endure forever.

“The qualities of a good prosecutor are as elusive and as impossible to define as those which make a gentleman. And those who need to be told would not understand it anyway. A sensitiveness to fair play and sportsmanship is perhaps the best protection against the abuse of power, and the citizens safety lies in the prosecutor who tempers zeal with human kindness, who seeks truth and not victims, who serves the law and not factional purposes, and who approaches his task with humility.”Robert H. Jackson, United States Supreme Court Justice, 1940This quote adorns the plaque with my badge affixed to it, given to me by Randy Sengel, Commonweatlth's Attorney for the City of Alexandria, Virginia when I left the office in 2003. It is a sentiment I've seen embodied in a happily large number of men and women over the course of my career, but perhaps never so profoundly as in a friend who passed away unexpectedly this week, Dan McCarthy.It's been observed in the legal community that, oftentimes, there's an inverse relationship between the skill and success of a trial attorney, and his or her skill and success as a human being. Simply put, some of the most effective and remarkably talented trial attorneys out there are walking disasters in their personal lives.Daniel McCarthy, Chief Trial Counsel and Director of Trial Training at the Bronx District Attorneys Office, was the very best trial lawyer I ever knew personally, and recognized as one of the best in the country. He was also a remarkable success as a human being. Dan could do both, and with what looked like effortless aplomb.I worked in the Bronx, where Dan was an ADA for 18 years, for a little less than two. When I contemplate my service there I sometimes feel the guilt of soldiers who, for whatever reason, spent very little time in a combat zone. I am grateful for the experience, but I hold my service cheap compared to friends, colleagues and giants like Dan who spent much of their careers in service in this good and fascinating, but often brutal and challenging community. Dan had every opportunity to leave prosecution almost 20 years ago and make a remarkably good living as a litigator in the private sector. But instead he went from one tough environment (Queens) to an arguably even tougher environment (the Bronx) in order to continue to seek justice and serve victims.Thankfully I knew Dan before and after BXDA, but during my time there he taught me things I still hold dear. My favorite example might be this one: ADA's, when they appear in court, usually announce their appearance for the "District Attorney." It was Dan who taught me to personalize my appearance to the good man who hired me. "He represents this community and he deserves your loyalty and respect," he said. "When you appear in court, say you're there on behalf of the office of Robert T. Johnson." It was a gesture I maintained when I appeared on behalf of then Attorney General Andrew M. Cuomo two years later.It was Dan- more than anyone else in my career, and I have had great mentors- who emphasized in deeply compassionate terms the reality that lingered behind the case folders. Lives are broken by crime and they are not put back together by criminal litigation. The dead are silenced and their potential truncated, leaving behind grieving loved ones who never fully recover. The wounded and paralyzed- mentally or physically- are at times left to navigate lives that can draw out like a blade in numbing, endless days of struggle. Victims fight nightmares, despair, hopelessness and rage, all long after the publicity is over, the juries are dismissed and the accolades are shared. Dan never let us forget this.The Bronx, at once magnificent and godforsaken, lush with green space and choked with urban density, home to centuries of history and yesterday's arrivals from every point on the globe, possessed of both world-class schools and grinding poverty, is itself a study in contradictions.When I think about it, I suppose Dan was also. He was a nationally known attorney with sobering responsibilities who was always ready to poke fun at himself and never too busy to brainstorm with a young ADA facing a first larceny trial. He was endlessly creative, pincer-like and pulverizing when proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, but hyper-ethical and deeply compassionate to everyone on both sides of the tragic cases he handled. He was erudite and analytical but fun-loving and folksy. The man could, very simply, do it all. His loss leaves an empty space in the American prosecution community and the lives of his friends and family that won't be filled. But he also leaves a legacy of decency, compassion and justice that will, in the spirit of true success, endure forever.

The Power of Two

In child abuse prosecution, it is all but axiomatic that a two year-old victim simply cannot describe her victimization to any legally usable degree. In most cases, toddlers that age can’t relate anything reliably. Facts that can be gleaned are disjointed, conflated with the product of imagination, or just impossible to follow. Most prosecutors, even if they’ve raised children themselves, won’t attempt to interview a two year-old. If the child is three, and fairly precocious, maybe. Two is just too young.But ADA Danielle Pascale is not most prosecutors.The Bronx District Attorneys Office, where I served for almost two years, is one of the most challenging in the country. The Bronx, despite its generally dismal image, is an interesting, diverse, and in some areas beautiful place to live and work. Its food, in neighborhood restaurants and corner delis, is fantastic. It is framed by magnificent waterways and huge, shaded parks. Its historical value and educational heritage are unmatched almost anywhere. Some Bronx neighborhoods are charming, tree-lined and friendly. But grinding poverty and social pathology deeply haunt other areas and still produce crime, while less now than in the hellscape of the 70’s and 80’s, in daunting amounts.Danielle is a product of the Bronx and serves in the Child Abuse and Sex unit where she’s been for nearly nine tough years. Her compassion for, love of, and raw skill with children are unmatched anywhere in my long experience in child protection. But sometimes, Danielle surprises even me.A few months before I left the office, a particularly horrific case arose that fell to Danielle. In a Bronx apartment, a toddler I'll call Jane stumbled out of her mother’s bedroom and into the living area she shared with her three older sisters. Jane’s lip was split, her hair disheveled, and her face bloody. Blood was later discovered in her underpants, reflecting a brutal injury to her vagina. The suspect, Jane’s mother’s boyfriend (I'll call him John), had been in the bedroom alone with the child and walked out a few seconds later. Jane’s sisters reacted quickly and called the police. Jane was taken to Jacobi Medical Center, an excellent Bronx hospital where child abuse is often investigated and treated. She was attended to by physicians and taken into protective custody. As part of a multi-disciplinary effort in the Bronx to get ADA’s involved early in child abuse cases, Danielle responded to Jacobi after Jane had been treated to see what could be done with the case.When Danielle encountered Jane, she was armed with nothing but the contents of her purse and her cell phone. She played with the girl for a couple of hours, interacting with her, building rapport, and (in the spirit of the team approach to child abuse) watching her and assessing her ability to describe what had been done to her. Given Jane’s age, this step is one most prosecutors would have skipped, believing it hopeless. Patient and tender interaction with an abused and traumatized child is its own absolute good, and the time Danielle spent with Jane wouldn’t have been wasted anyway. But what emerged from that effort was remarkable. Danielle was impressed with the cognitive level of development the child was showing, and eventually decided to use the video function on her cell phone to see how Jane would respond to seeing herself recorded. She loved it, and recited her name, her ABC’s, and eventually her knowledge of basic body parts like her nose, mouth and eyes. Then Danielle put the phone away. Careful to frame the question fairly and not suggest anything to the child one way or the other as she had been trained, Danielle asked Jane if she knew why she was at the hospital. Jane nodded.“John hurt my cookie with his hand,” she said. Danielle asked Jane if she knew where on her body her 'cookie' was. Jane pointed to her genital area. And who was John? Mommy’s boyfriend, Jane knew.New York law allows something called unsworn testimony with children who are too young to be properly sworn as witnesses before tribunals like a Grand Jury or a court of law. Their testimony can still be considered as long as it is corroborated with other admissible evidence. Danielle’s first challenge once charges were brought against John would be a presentation to one of the Bronx’s sitting grand jury panels. She knew that the physician and child abuse specialist on her team could testify compellingly to the injuries to Jane’s vagina and face. There was no question that she had been hideously attacked; the only question was who did it. The circumstantial evidence was very good to begin with- the suspect had been alone in the room with the child and had walked out almost immediately after her in view of Jane’s sisters.But Danielle got far more than that. A child less than three years of age, whom she had known for less than an afternoon, told her in no uncertain terms who had harmed her and how. Danielle would now make sure Jane told the grand jurors who would hear the case against her abuser. The testimony would be unsworn, but with the other evidence it could be considered if it could be elicited. Seeing how well Jane had reacted to being video recorded, she arranged for a camera crew the next day to come to Jacobi, and before the camera asked Jane the same simple questions. The jurors saw this evidence in context with the rest and passed the case on to the next level of prosecution, where it remains pending.My friend accomplished the nearly impossible through patience, deftness, compassion, and an almost ethereal ability to reach and draw from a child far too young to speak on her own. In so doing, she gave Jane something the child had likely never experienced and probably won’t again for some time to come: Power. Her power to express herself yielded a simple and profound truth that, communicated to players in a system of justice, went far to seal a criminal case against the man who brutalized her. A two year-old shouldn’t need that kind of power, but in her case it was utterly crucial to ensure justice and protect herself, her family and other potential victims like her. This empowerment was certainly lost on Jane in the moment. But God willing, echoes of it will cascade throughout her life and shape the woman she’ll become. For Danielle, it was all in a day’s work.

In child abuse prosecution, it is all but axiomatic that a two year-old victim simply cannot describe her victimization to any legally usable degree. In most cases, toddlers that age can’t relate anything reliably. Facts that can be gleaned are disjointed, conflated with the product of imagination, or just impossible to follow. Most prosecutors, even if they’ve raised children themselves, won’t attempt to interview a two year-old. If the child is three, and fairly precocious, maybe. Two is just too young.But ADA Danielle Pascale is not most prosecutors.The Bronx District Attorneys Office, where I served for almost two years, is one of the most challenging in the country. The Bronx, despite its generally dismal image, is an interesting, diverse, and in some areas beautiful place to live and work. Its food, in neighborhood restaurants and corner delis, is fantastic. It is framed by magnificent waterways and huge, shaded parks. Its historical value and educational heritage are unmatched almost anywhere. Some Bronx neighborhoods are charming, tree-lined and friendly. But grinding poverty and social pathology deeply haunt other areas and still produce crime, while less now than in the hellscape of the 70’s and 80’s, in daunting amounts.Danielle is a product of the Bronx and serves in the Child Abuse and Sex unit where she’s been for nearly nine tough years. Her compassion for, love of, and raw skill with children are unmatched anywhere in my long experience in child protection. But sometimes, Danielle surprises even me.A few months before I left the office, a particularly horrific case arose that fell to Danielle. In a Bronx apartment, a toddler I'll call Jane stumbled out of her mother’s bedroom and into the living area she shared with her three older sisters. Jane’s lip was split, her hair disheveled, and her face bloody. Blood was later discovered in her underpants, reflecting a brutal injury to her vagina. The suspect, Jane’s mother’s boyfriend (I'll call him John), had been in the bedroom alone with the child and walked out a few seconds later. Jane’s sisters reacted quickly and called the police. Jane was taken to Jacobi Medical Center, an excellent Bronx hospital where child abuse is often investigated and treated. She was attended to by physicians and taken into protective custody. As part of a multi-disciplinary effort in the Bronx to get ADA’s involved early in child abuse cases, Danielle responded to Jacobi after Jane had been treated to see what could be done with the case.When Danielle encountered Jane, she was armed with nothing but the contents of her purse and her cell phone. She played with the girl for a couple of hours, interacting with her, building rapport, and (in the spirit of the team approach to child abuse) watching her and assessing her ability to describe what had been done to her. Given Jane’s age, this step is one most prosecutors would have skipped, believing it hopeless. Patient and tender interaction with an abused and traumatized child is its own absolute good, and the time Danielle spent with Jane wouldn’t have been wasted anyway. But what emerged from that effort was remarkable. Danielle was impressed with the cognitive level of development the child was showing, and eventually decided to use the video function on her cell phone to see how Jane would respond to seeing herself recorded. She loved it, and recited her name, her ABC’s, and eventually her knowledge of basic body parts like her nose, mouth and eyes. Then Danielle put the phone away. Careful to frame the question fairly and not suggest anything to the child one way or the other as she had been trained, Danielle asked Jane if she knew why she was at the hospital. Jane nodded.“John hurt my cookie with his hand,” she said. Danielle asked Jane if she knew where on her body her 'cookie' was. Jane pointed to her genital area. And who was John? Mommy’s boyfriend, Jane knew.New York law allows something called unsworn testimony with children who are too young to be properly sworn as witnesses before tribunals like a Grand Jury or a court of law. Their testimony can still be considered as long as it is corroborated with other admissible evidence. Danielle’s first challenge once charges were brought against John would be a presentation to one of the Bronx’s sitting grand jury panels. She knew that the physician and child abuse specialist on her team could testify compellingly to the injuries to Jane’s vagina and face. There was no question that she had been hideously attacked; the only question was who did it. The circumstantial evidence was very good to begin with- the suspect had been alone in the room with the child and had walked out almost immediately after her in view of Jane’s sisters.But Danielle got far more than that. A child less than three years of age, whom she had known for less than an afternoon, told her in no uncertain terms who had harmed her and how. Danielle would now make sure Jane told the grand jurors who would hear the case against her abuser. The testimony would be unsworn, but with the other evidence it could be considered if it could be elicited. Seeing how well Jane had reacted to being video recorded, she arranged for a camera crew the next day to come to Jacobi, and before the camera asked Jane the same simple questions. The jurors saw this evidence in context with the rest and passed the case on to the next level of prosecution, where it remains pending.My friend accomplished the nearly impossible through patience, deftness, compassion, and an almost ethereal ability to reach and draw from a child far too young to speak on her own. In so doing, she gave Jane something the child had likely never experienced and probably won’t again for some time to come: Power. Her power to express herself yielded a simple and profound truth that, communicated to players in a system of justice, went far to seal a criminal case against the man who brutalized her. A two year-old shouldn’t need that kind of power, but in her case it was utterly crucial to ensure justice and protect herself, her family and other potential victims like her. This empowerment was certainly lost on Jane in the moment. But God willing, echoes of it will cascade throughout her life and shape the woman she’ll become. For Danielle, it was all in a day’s work.

Tough Job, Tougher Women

Sue Rotolo’s eyes are the first thing you’ll notice about her; they are almost impossibly blue, and glow lightly beneath red hair. Her smile is easy and warm, and she has an enviable air of serenity, whether in the presence of an eight year-old rape victim about to be forensically examined or an aggressive attorney attempting to lock her down on cross examination.It’s a good thing. That Zen-like calmness serves her well. In the clinic, her job as a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (with the odd acronym SANE) is to treat patients who are victims of sexual violence. In the courtroom, she testifies as an expert to what she observed and what it might mean legally. Ask her which job is more difficult and she’ll likely tell you the courtroom; it’s less predictable and more brutal. It’s at times a tongue in cheek response, but it’s no less true even if a little bit funny.Rape, after all, doesn’t usually happen between 9 and 5 weekdays. SANEs are torn from their beds, their loved ones and their lives to provide hands-on care to people suffering some of the worst trauma imaginable. It happens in every combination of off hours, holidays, weather and traffic. In the crush and tangle of Northern Virginia where I learned from Sue the business of forensic nursing, a trip to Inova Fairfax Hospital can take hours from two towns over in the wrong circumstances. The patients are at times tragically young or old (Sue’s youngest was about three months). Some are combative, some intoxicated. Some giggle. Some beg for relief from any number of things that haunt them, real and imagined. Sue, and the nurses who work for her, see them all.And nevertheless, it’s us, the lawyers, who create the ultimate crucible for a woman in Sue’s crew who wants to be a SANE. It’s the contact sport of criminal litigation- often at its most bitter and belligerent in cases of sexual assault- that drives many hopeful forensic nurses out of the business. Attorneys often treat them, because they’re “just nurses,” with far less than the respect they merit (most doctors, unless they specialize in forensics, are much less valuable on the stand in a rape case than an experienced SANE). They’re attacked mercilessly for being everything from sorority-like “little sisters” of the police and prosecution to man-hating zealots or glorified candy-stripers. Every cruel and gender-based stereotype that can be slung at them from the male dominated world of trial law is done so. The successful ones realize early on that testifying is yet another skill- completely discrete from anything else one does as a nurse- that must be mastered in order to survive. Sue has one iron rule- no crying on the witness stand. I worked directly with her nurses for years and never saw it broken, even when I knew I’d have been reduced to sobs had I been where they were.The ones who do survive the process make healing differences in the lives of their patients few will ever match. Rape has always been difficult to report, but prior to SANE programs (an adjunct of the woman's and victims movements of a generation ago) it was at times tantamount to a re-victimization. Victims waited for hours, triaged behind whatever nightmares took precedence in the ER they found their way to. Many physicians were unable or barely willing to conduct the examinations both for treatment and possible evidence collection, and they wanted no part of the legal process. Victims were judged, ignored or even threatened with arrest depending on how they presented. It was more than wrong, more than something that worsened experiences and deepened the pain. It also killed cases and drove victims underground. That allowed attackers to escape justice and rape again; most rapists don’t stop at one.The idea of SANE programs is to specially train nurses to treat and examine patients whose chief complaint is sexual assault, and to evaluate the body as a crime scene, collecting potential evidence for investigation and trial. As an invaluable plus, the exams are conducted in a safe, private and dignified setting where the person at the center of the case can begin to heal, and regroup. With the help of victim advocates who provide the emotional support and ties to other services they need, the process, when it’s done right, produces a better, stronger witness for us and a sex assault survivor with a fighting chance at looking at life at least similarly to how she did before.It’s still an evolving process, and I’ve been blessed to work with some of the finest women I’ve ever known in the building and sustaining of the programs and their interaction with the legal system. From Jen Markowitz in Ohio, Eileen Allen in New Jersey, Tara Henry in Alaska, Pat Speck in Tennessee, Jen Pierce-Weeks in New Hampshire, Jacqui Calliari in Wisconsin, Diana Faugno in California, Elise Turner in Mississippi, Linda Ledray in Minnesota, Karen Carroll in New York and dozens of others, I’ve learned more about the relevant anatomy and reproductive health then I ever thought possible, and we’ve broken bread and self-medicated together in more places than I can remember.But it was Sue, with her bright eyes, warm smile and unflappable mien who taught me with plain speech how to drop my blushes, learn the anatomy, pronounce the terms, protect the truth through her testimony, and do my job.What Sue has done literally thousands of times is probably best exemplified by a story she sometimes relates in training regarding an eight year-old girl who had been sexually abused by a family member. After being examined by Sue in an invasive but tender and careful manner, the child asked her how bad she looked inside now that she had been made bad by what had happened to her.“Honey,” Sue said, “you are perfect inside. And you’re perfect outside.”That child may forget the lawyers, the judges, the police officers and the numbing, contentious process that played out above her. She will never forget the abuse. But God willing, she also won’t forget the blue-eyed lady with the stethoscope; the one who reminded her of the most important thing of all.

Sue Rotolo’s eyes are the first thing you’ll notice about her; they are almost impossibly blue, and glow lightly beneath red hair. Her smile is easy and warm, and she has an enviable air of serenity, whether in the presence of an eight year-old rape victim about to be forensically examined or an aggressive attorney attempting to lock her down on cross examination.It’s a good thing. That Zen-like calmness serves her well. In the clinic, her job as a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (with the odd acronym SANE) is to treat patients who are victims of sexual violence. In the courtroom, she testifies as an expert to what she observed and what it might mean legally. Ask her which job is more difficult and she’ll likely tell you the courtroom; it’s less predictable and more brutal. It’s at times a tongue in cheek response, but it’s no less true even if a little bit funny.Rape, after all, doesn’t usually happen between 9 and 5 weekdays. SANEs are torn from their beds, their loved ones and their lives to provide hands-on care to people suffering some of the worst trauma imaginable. It happens in every combination of off hours, holidays, weather and traffic. In the crush and tangle of Northern Virginia where I learned from Sue the business of forensic nursing, a trip to Inova Fairfax Hospital can take hours from two towns over in the wrong circumstances. The patients are at times tragically young or old (Sue’s youngest was about three months). Some are combative, some intoxicated. Some giggle. Some beg for relief from any number of things that haunt them, real and imagined. Sue, and the nurses who work for her, see them all.And nevertheless, it’s us, the lawyers, who create the ultimate crucible for a woman in Sue’s crew who wants to be a SANE. It’s the contact sport of criminal litigation- often at its most bitter and belligerent in cases of sexual assault- that drives many hopeful forensic nurses out of the business. Attorneys often treat them, because they’re “just nurses,” with far less than the respect they merit (most doctors, unless they specialize in forensics, are much less valuable on the stand in a rape case than an experienced SANE). They’re attacked mercilessly for being everything from sorority-like “little sisters” of the police and prosecution to man-hating zealots or glorified candy-stripers. Every cruel and gender-based stereotype that can be slung at them from the male dominated world of trial law is done so. The successful ones realize early on that testifying is yet another skill- completely discrete from anything else one does as a nurse- that must be mastered in order to survive. Sue has one iron rule- no crying on the witness stand. I worked directly with her nurses for years and never saw it broken, even when I knew I’d have been reduced to sobs had I been where they were.The ones who do survive the process make healing differences in the lives of their patients few will ever match. Rape has always been difficult to report, but prior to SANE programs (an adjunct of the woman's and victims movements of a generation ago) it was at times tantamount to a re-victimization. Victims waited for hours, triaged behind whatever nightmares took precedence in the ER they found their way to. Many physicians were unable or barely willing to conduct the examinations both for treatment and possible evidence collection, and they wanted no part of the legal process. Victims were judged, ignored or even threatened with arrest depending on how they presented. It was more than wrong, more than something that worsened experiences and deepened the pain. It also killed cases and drove victims underground. That allowed attackers to escape justice and rape again; most rapists don’t stop at one.The idea of SANE programs is to specially train nurses to treat and examine patients whose chief complaint is sexual assault, and to evaluate the body as a crime scene, collecting potential evidence for investigation and trial. As an invaluable plus, the exams are conducted in a safe, private and dignified setting where the person at the center of the case can begin to heal, and regroup. With the help of victim advocates who provide the emotional support and ties to other services they need, the process, when it’s done right, produces a better, stronger witness for us and a sex assault survivor with a fighting chance at looking at life at least similarly to how she did before.It’s still an evolving process, and I’ve been blessed to work with some of the finest women I’ve ever known in the building and sustaining of the programs and their interaction with the legal system. From Jen Markowitz in Ohio, Eileen Allen in New Jersey, Tara Henry in Alaska, Pat Speck in Tennessee, Jen Pierce-Weeks in New Hampshire, Jacqui Calliari in Wisconsin, Diana Faugno in California, Elise Turner in Mississippi, Linda Ledray in Minnesota, Karen Carroll in New York and dozens of others, I’ve learned more about the relevant anatomy and reproductive health then I ever thought possible, and we’ve broken bread and self-medicated together in more places than I can remember.But it was Sue, with her bright eyes, warm smile and unflappable mien who taught me with plain speech how to drop my blushes, learn the anatomy, pronounce the terms, protect the truth through her testimony, and do my job.What Sue has done literally thousands of times is probably best exemplified by a story she sometimes relates in training regarding an eight year-old girl who had been sexually abused by a family member. After being examined by Sue in an invasive but tender and careful manner, the child asked her how bad she looked inside now that she had been made bad by what had happened to her.“Honey,” Sue said, “you are perfect inside. And you’re perfect outside.”That child may forget the lawyers, the judges, the police officers and the numbing, contentious process that played out above her. She will never forget the abuse. But God willing, she also won’t forget the blue-eyed lady with the stethoscope; the one who reminded her of the most important thing of all.

Thanks, Detective Perez